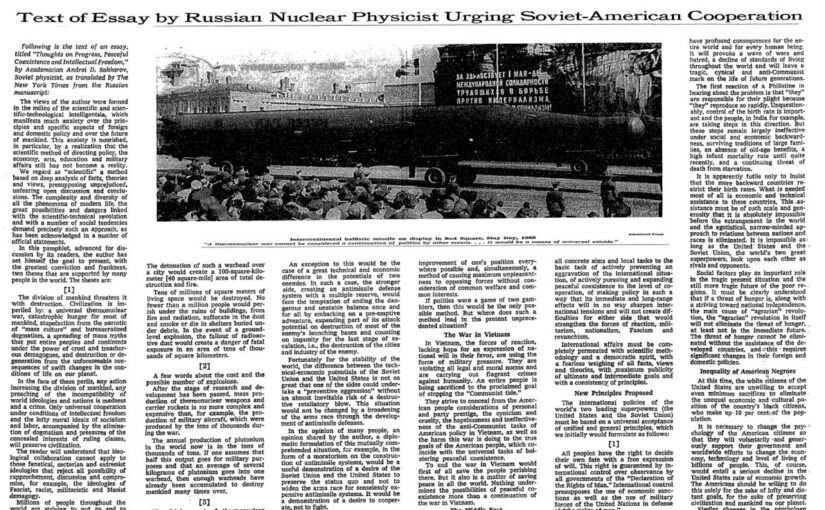

Fifty-seven years ago today, on 22 July 1968, Sakharov’s “Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom” sent waves around the world. The New York Times chose to publish the entire English version of the text, covering three full pages of the newspaper. Westerners were shocked to hear a voice of reason, with an emphasis on common values, coming from behind the Iron Curtain. The Soviet officials fumed, unable to understand how a Soviet citizen, whom they showered with awards and prizes, who was granted access to the highest level of services that money could not buy in the USSR, dared to risk all of that for a vague concept of ‘intellectual freedom.’

To be fair, Sakharov, who did allow the leak of his manuscript to the West, at first attempted to use his privileged channels of communication to engage in discussion with the CPSU Central Committee members and the Soviet premier, Leonid Brezhnev. He worked on his manuscript in open, with his Arzamas-16 secretary tasked with typing up his handwritten text. He read some parts of it to his science director, Yuli Khariton, a brilliant Cambridge-educated physicist. Khariton was petrified. Sakharov also read his manuscript and discussed his publication plans with Klavdia, his first wife, who by then was succumbing to terminal cancer. Just like Khariton, Klavdia expressed her fears; yet, she showed steadfast support to her husband, telling him he had a right to say what he believed in.

Sakharov felt the urgency of such a discussion in light of the recent Cuban Missile Crisis and rapid technological advances in nuclear warfare. Convinced that international security cannot be achieved without intellectual freedom and human rights, Sakharov sent his manuscript to the top echelon of the Soviet leaders, inviting them to start a dialogue with their Western counterparts.

Met with a wall of silence, Sakharov realized that he had no other choice but to draw attention to the matter from a different angle. That year, Sakharov’s Reflections became the third most printed book in the world.

Sakharov’s signature foresight is on display in “Reflections”: well ahead of his time, he was able to identify and analyze many problems that the world would face some half a century later as well as predicting the use of the Internet and AI.