“The dissident movement contributed significantly to the hollowing out of the legitimacy of the Soviet regime, which in turn made the system exceptionally brittle”

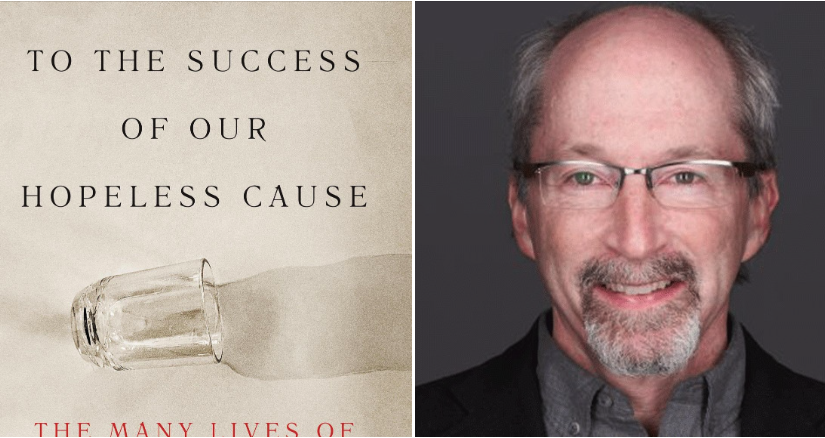

From a new book, “To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause” by Benjamin Nathans

Benjamin Nathans, a professor of history at University of Pennsylvania, just published a new book, “To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause”, examining the many faces of the Soviet dissident movement. It is a great volume, presenting myriads of data combined with deep analysis.

We are grateful to prof Nathans for finding time to share his insights and answer a few questions for our post. We enjoyed reading the book and hope our readers will do too!

The ASF: Sergey Kovalev, writing about Andrei Sakharov, posed a rhetorical question: “there were other scientists of outstanding intelligence; Sakharov was not the only one awarded three stars of Hero of Socialist Labor. They must have understood the nature of the USSR – why did they not protest? Perhaps, not as sharply as Sakharov but still. If only 10% of the USSR Academy of Sciences raised their concerns it would have made a difference.” From that perspective, how would you explain the type of persons who became Soviet dissidents? Could there be more people joining in voicing their dissenting views?

Benjamin Nathans: A high proportion of Soviet dissidents were scientists, but the vast majority of Soviet scientists did not become dissidents. I doubt that sheer intelligence, even the extraordinary kind one finds in highly accomplished physicists such as Andrei Sakharov, was the decisive factor in whether a given person joined the dissident movement. My impression, based on dozens of dissident accounts, is that a person’s response to a potentially morally compromising situation – being pressured by the KGB to inform on one’s peers, for example – was the most common point of departure for dissenting activity. The writer Andrei Sinyavsky called these situations “stumbling blocks,” and millions of Soviet citizens encountered them over the course of their lives. Those who became dissidents typically reacted to such situations from a position of high, uncompromising moral principle – and in many cases, those principles were inculcated as part of their Soviet education. People of high intelligence who understood the nature of the Soviet system could always find reasons not to protest – by telling themselves that nothing would ever change, by devoting themselves exclusively to their chosen profession, by assuming that politics was by nature a dirty business. Intellectuals are very good at coming up with reasons to justify their actions – or inaction.

The ASF: A “hopeless cause”: in your opinion, does it refer more to the chances of the dissident movement to make a difference or to the inevitability of history path? (Sakharov said, “a history mole digs undetected”, suggesting that the change may be around the corner at any moment, no matter how unlikely it may appear.

BN: “Hopeless cause” comes from the dissidents themselves, from their favorite toast. It captures, I think, their deep sense of irony about the prospects of their movement. There is a persistent current of fatalism in Russian and Soviet culture, including the dissident element of that culture. The remarkable thing is that dissidents nonetheless persisted in their campaign to make the Soviet government obey its own laws, including the civil liberties guaranteed by the Soviet constitution. They attempted to steer a path between what they called “dogmatic pessimism” (i.e., fatalism) and “pathological optimism.” Or as Andrei Dmitrievich put it, “There is a need to create ideals even when you can’t see any way to achieve them, because if there are no ideals, there can be no hope and one would be left completely in the dark, in a hopeless blind alley.”

The ASF: Coming back to the previous question, how considerable, in your opinion, was the impact of the dissidents’ activities on bringing about Gorbachev’s Perestroika?

BN: Gorbachev wrote in his memoirs that the dissident movement “left traces, if not in the structures [of Soviet life], then in people’s minds” – including, presumably, his own. It is impossible to quantify the impact of the “rights defenders” on Gorbachev and other reformers, but the overlap in vocabulary, from “glasnost’” to “democratization,” is striking. I believe the dissident movement contributed significantly to the hollowing out of the legitimacy of the Soviet regime, which in turn made the system exceptionally brittle. Dissidents shattered the fourth wall of the USSR’s performance of its own ideology. But it’s important to recognize that the central goal of Gorbachev’s perestroika was to reform the Soviet economy – an arena about which the dissidents had said relatively little.

The ASF: Why, as you suggest, the dissidents’ influence in the Russian politics in the 1990s was so limited? How was it different from the other countries of the socialist bloc, like Poland?

BN: Most Soviet dissidents insisted that their movement was apolitical because it was strictly grounded in law and human rights. They did not aspire to capture let alone destroy the Soviet state. By the 1980s, more than half the movement had been forced to leave the USSR, and most of those who remained were in labor camps or internal exile. But more importantly, many dissidents considered any kind of involvement in government work to be inherently morally compromising. The idea of the nobility of public service in the form of running for this or that office was practically non-existent. When Sakharov successfully ran for the newly created Congress of People’s Deputies in 1989, he was roundly criticized by many dissidents. Sergei Kovalev and Ludmilla Alexeyeva faced similar criticisms when they took on official roles in the 1990s. By contrast, East European dissidents such as Lech Walesa and Vaclav Havel were elevated to the highest offices of Poland and Czechoslovakia, respectively, with widespread popular support by their fellow dissidents and ordinary citizens alike. Dissidents in those countries were less socially isolated than their counterparts in the Soviet Union.

The ASF: Do you believe that the legacy of the Soviet dissident movement can be instructive for the Russian opposition to the Putin’s regime?

BN: I do. The rule of law is an indispensable component of any effort to place limits on the power of the Russian state, indeed of any state. More generally, the courage and moral clarity exhibited by many Soviet dissidents is instructive not just for members of today’s Russian opposition, but for all of us. At the same time, opposition activists in post-Soviet Russia have made a crucial breakthrough: they do not position themselves as apolitical. They openly declare the right to engage in political activity, including running for public office – or rather, they did so until the Putin regime made that impossible. Another crucial legacy of the Soviet dissident movement, one that must be overcome, is its isolation from the rest of the population. Democratic reforms cannot succeed if they do not have support from the demos – the people themselves.

The ASF: How relevant in your opinion is the Soviet dissidents’ experience in confronting the authoritarian regime to the US reading audience?

BN: The drama of the Soviet dissident movement – its relations with the Soviet state and the West, its internal tensions and transformations – are, to my mind, inherently fascinating. As for whether American readers will share that view – we will see how well my book sells!

See also:

Benjamin Nathans’ book talk and reading at Politics and Prose bookstore in Washington, D.C (YouTube)